|

| Multimedia Gallery

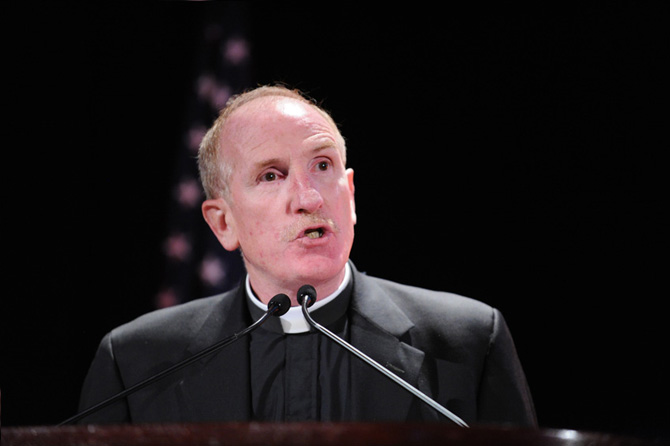

Centennial Gala Keynote Address | | Below is the text to the Keynote address offered at the Regis High School Centennial Gala by Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J. '67, President of Fordham University. |

| |

|

| |

"Of those to whom much is given, much is expected."

"Dearest Lord, teach me to be generous.

Teach me to serve You as You deserve.

To give and not to count the cost."

Bishop Caggiano, Fr. Cecero, Fr. Judge, Fr. Gavin, Fr. McClain, Mr. Labbat, Mr. Minson, and Noble Hearts all.

Ah, fair Regis! My friends, as you know, the problem with Regis is that its hype never lived up to the reality of the Regis experience. Now that's saying something. As you know, the Regis name has a way of inspiring a touch of awe whenever it is dropped in the course of a conversation. And let's be honest. Regians can tend to walk with a bit of swagger knowing that the name has a touch of cachet to it. But let's also be honest and admit that the hype about Regis never really lived up to the experience we had there. To be sure, Regis was a remarkable experience. It was not, however, an experience for the faint of heart. Nor should it have been. After all, it is a school that has the special mission of educating students who seem to be described in the words from the Gospel of Luke with which I began my remarks: "those to whom much has been given." It is also a school that has never lost sight of the second part of the Lord's statement: of those to whom God has—for reasons known only to Himself—given much, much is expected. Therefore, it is a school that has worked mightily to teach its students that the proper response to God's gifts is not a swaggering arrogance, but rather a deep and humble gratitude that shows itself in both a broad and celebratory exploration of the world that God has made and a life of self-emptying generosity that is worthy of the men for others that they aspire to be.

The school has always had three different teaching staffs devoted to forming men with keen minds and generous hearts: the faculty, our classmates and the city. A word about each of them. As for the faculty, they never let us rest on the laurels that the outside world was more than willing to throw at us. Quite the opposite. They challenged and cherished us in equal measure. In fact, they were able to challenge us precisely because we knew that they cared deeply for us. And challenge us they did. Under their firm but loving guidance, we learned how to wrestle with ideas, and to take delight in playing with language. We fought physics to a standstill. With them at our side, we made friends with Homer, Virgil, Horace and Catullus. We were welcomed into the small fraternity who knew that the secret to a happy life was to be found in the knowledge that Greek had three voices: active, passive and middle. (Who knew? We did, of course, but I think I could have been a happy man living with only the active and passive voices. Don't get me started on the number of tenses found in the classics. To tell you the truth, tenses made me tense for four years. And I was deeply disappointed when I learned that "the future perfect" referred to a tense and not to canonization.) We were taught how to sing the first lines of the Iliad, the Odyssey and the Aenied to the tune of Stars and Stripes Forever to experience the power and beauty of dactylic hexameter.

(ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλὰ πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσεν•

or, in transliterated format: [singing] Andra moi ennepe Mousa, polutropon, hos mala polla Planchthe epei Troies hieron ptoliethron epersen.

We hung out with Chaucer, Shakespeare and Milton. We walked on the wild side with F. Scott Fitzgerald. We sailed with both Melville and Hemingway. We roared and raged with Dylan Thomas. We suffered depression with Eugene O'Neill. Our hearts soared with John XXIII. We anguished our way through the mysteries of algebra, geometry, trig and pre-calculus. In the process, our hearts were stretched, our minds expanded, and our horizons broadened. Sometimes our heads ached. Sometimes we wondered if we were being prepared to live lives of meaning in the twentieth century, or being prepared to become Roman emperors or contestants on Jeopardy.

Of course, the faculty were not our only teachers. The lessons they taught us were supplemented by those we learned from our classmates. Hailing from the splendor of Stuyvesant Town, the exotic reaches of the Rockaways, Bay Ridge, Sheepshead Bay, foreign ports of call like Staten Island and New Jersey, and the leafy precincts of Riverdale, Westchester and Connecticut, our classmates became dear friends, mentors and colleagues in the search for wisdom. The suburbanites astounded the city-dwellers among us with stories of homes surrounded by lawns and trees. (We were dumbstruck.) We treated their stories of commutes on ferries or on trains that had romantic departure times with the same awe (or was it disbelief) with which we treated Homer's account of Odysseus' travels. In league with them, we ventured out into the City and discovered the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Frick, the MOMA, the Whitney and Lincoln Center. Together, we debated the major issues of the day, and some of the minor issues of life at Regis. (Into the former category I would place the lessons in love, service and compassion that we learned from our service projects in the City. Into the latter category I would place the morality of selling elevator keys and pool passes to freshmen, and whether or not the members of the Hearn, the Regis equivalent of Skull and Bones, should get varsity jackets.) Through it all, over pizza or on the bus and boat rides to Bear Mountain, our classmates challenged, cajoled, pushed, consoled, and cheered us on. They also inspired us never to settle for things as they were. Rather, by word, deed and shining example, they called us to push out into the deep. Thanks to them and the faculty who seemed intent on calling us to a greatness that we never thought we could achieve, we discovered that there is no hunger like the taste of truth, no thirst like the desire for justice, and no greater joy than that found in the service of others. In short, our intellectual and moral compasses were set at Regis.

At the end when, with a final burst of exuberant (and slightly eccentric) extravagance we graduated wearing white dinner jackets, crimson bow ties and cummerbunds rather than standard-issue caps and gowns, we knew that Regis had given us a peerless but bothersome education. What do I mean? Simply this: Regis bestowed upon us a desire to seek not just excellence, but bothered excellence. Again, what do I mean? Regis made us men who loved learning but sent us forth with the blessedly nagging suspicion that we didn't know everything and the burning conviction that the truly good life is one that is spent in service. (We even had a few lines of poetry to describe how we felt as we walked through the Tunnel for the last time. Fittingly enough, they are taken Tennyson's Ulysses (another ancient Greek by way of a Romantic poet's imagination): we were propelled forward with a desire "to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.")

Every Regian is haunted by the realization that his life was transformed by an unearned gift of pure grace from a woman whom we only knew as The Foundress. We were not the children of privilege. Far from it. We were and are, however, the adopted sons of generosity. And what boundless and inexplicable generosity it was. Although the Foundress never met us, she loved us. Although she never knew us, she believed in us. Although she never saw us, she nurtured high hopes for us. Ultimately, she and her family gave us all that they had so that we might have and lead lives filled with meaning and purpose.

I suspect that I am not the only Regian who has felt a deep desire to thank her personally for all that she did to transform our lives. Therefore, moved by the faith, hope and love that she had for all of us, this past Thursday, I took an Irish holiday. That is to say, I visited Old (or First) Calvary Cemetery in Queens to find her grave. After trekking up and down among the ancient graves in a steady rain for forty-five minutes without finding the family vault, I was on the verge of giving up and going home. Then, suddenly I turned a corner and came upon a stately columned mausoleum that bore her family name. I put down my umbrella, held my breath and peered through the windows of the bronze doors of the mausoleum. And there I saw it: her name. I trembled. Then, I stepped back and prayed. To be honest, I was not sure if I was praying to her or for her. But I can tell you this: I spoke to her from the heart--but not from my own heart alone. No. No. I told her that I spoke for every boy whose life had been forever changed and transformed by the unmerited gift that she had given to him. I spoke for every Noble Heart who ever walked through the Tunnel and discovered an entirely new world in and through the school that she had founded in memory of the husband who awaits the Resurrection just next to her. On your behalf, I thanked her. I assured her that even though we had never known her name, we tried to live lives worthy of the love that she had for us, the faith that she had in us and the hopes that she nurtured for all of us. I also asked her to pray that we might always be sons of fair Regis in deed and not only in name. That is to say, I asked her to pray that like herself, we might know how to give and not to count the cost, to labor and not to ask for any reward save that of knowing that we do God's will—and do it for His greater glory. As I was praying, the rain stopped and the leaden skies cleared slightly. My work, however, was not done. Before leaving, I bent down and left a small gift in your name on the threshold of her tomb: a bouquet of red and white roses. I bowed in homage, reverently touched the door of the mausoleum and raised my hand to make the sign of the cross to bless the woman who had filled our lives with blessings beyond measure. Then, I turned and walked back to the car through the quiet graveyard with an even greater sense of gratitude than I had had when I began my pilgrimage of thanksgiving.

My friends, with TS Eliot, my end is my beginning. "Of those to whom much is given, much is expected." As Regians and therefore as the sons of generosity, our response to these words must always be to say, "Teach me to be generous. Teach me to serve You as You deserve. To give and not to count the cost. To fight and not to heed the wounds. To toil and not to seek for rest. To labor and not to ask for any reward save that of knowing that I do your will. Amen." |

|