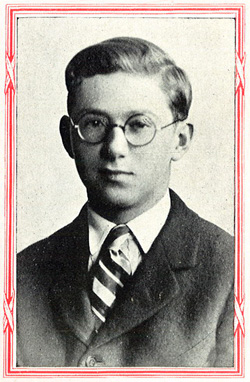

Frank S. Nugent ’25 made his career as a film critic and screenwriter, beginning in 1929 and lasting until his death in 1965. He began his career with

The New York Times as a reporter in 1929, before taking over as the paper’s motion picture editor and critic in 1936.

Nugent’s reviews often included a clever phrase or a pun and made for entertaining reading. That would have been no surprise to his classmates. In fact, the class description for him in the 1925 Regian included the following profile: “The class poet, the chronic joke-teller, the man with the ready and infectious laugh—that’s Frank... Although ‘Nuch’ achieved some renown by his famous remark “Thank God, I’m an atheist,” he derived his greatest fame when he applied the Child Labor Laws to JUG and claimed this incarceration was illegal.”

The wit and humor his classmates adored remained with him in his professional career. For example, on reviewing The Wizard of Oz (1939) Nugent wrote, “It is all so well-intentioned, so genial and so gay that any reviewer who would look down his nose at the fun-making should be spanked and sent off, supperless, to bed.”

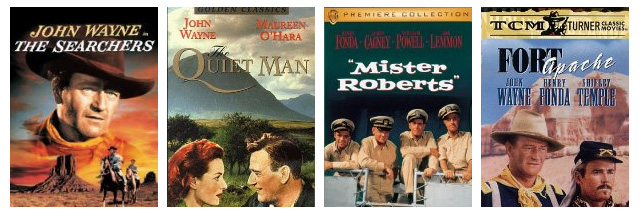

Nugent penned close to one thousand reviews for the New York Times before leaving journalism for Hollywood. During that time, he authored 21 film scripts, some of which were for famed director John Ford. Ford found Nugent much to his liking, and Nugent quickly became Ford's most frequent partner, collaborating on 11 pictures during their 15 years together.

Of his long association with Ford, Nugent once wrote: “I have often wondered why Ford chose me to wrote his cavalry films. I had been on a horse but once—and to our mutual humiliation. I had never seen an Indian. My knowledge of the Civil War extended only slightly beyond the fact that there was a North and a South, with West vulnerable and East dealing. I did know a Remington from a Winchester—Remington was the painter. In view of all this, I can only surmise that Ford picked me for Fort Apache as a challenge.”

Nugent occasionally ventured out from under Ford's wing to work with other great directors, including Robert Wise (Two Flags West, 1950), Otto Preminger (Angel Face, 1953) and Raoul Walsh (The Tall Men, 1955). But his most famous works came from his time with Ford. Nugent received an Academy Award nomination in 1953 for the screenplay of The Quiet Man. He won the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Written American Comedy twice in his career: in 1955 for Mister Roberts and in 1956 for The Quiet Man. He was also nominated for that same award two other times in his career: in 1949 for Fort Apache and in 1950 for She Wore A Yellow Ribbon.

Nugent served as the President of the Writers Guild of America, West from 1957 to 1958 and served as its representative on the Motion Picture Industry Council from 1954 to 1959. He also served as chairman of the building fund committee from 1956 to 1959, overseeing the construction of its headquarters in Beverly Hills.

Above: Nugent wrote the screenplays for some classic movies including (from left to right) The Searchers (1956), The Quiet Man (1952), Mister Roberts (1955), and Fort Apache (1948). (source: imdb.com)

The Writers Guild of America, West ranks Nugent’s screenplay for The Searchers (1956) among the top 101 screenplays of all time. It was named the Greatest Western of all time by the American Film Institute in 2008, and it placed 12th on the American Film Institute's 2007 list of the 100 Greatest American Films. In 2013, The Quiet Man was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being culturally and historically significant.

The 1925 Regian concludes with a farewell attributed to “F. S. N.” We can only assume it was authored by Frank S. Nugent, the “class poet” as referred to by his peers. A reprint of that farewell text is provided below.

“You have read here the melodies we played on Boyhood’s lyre, John and Sorrow, Humor, Friendship, Love,—you have found among them all the themes that touch and quicken, or lay heavy upon the human heart. We did not think much of them when we played them; we threw them aside with the quick petulance of childhood. Only in the light of parting did we perceive something of their true worth. And we made haste to gather them up,—broken chords, single plaintive notes, crescendo’s and diminuendo's,—we have collected all the precious fragments we could reclaim, and we have stored them in our Memory Book. For we want to have them at hand always; we want them to remind us always of the happy hours-on-hours we have spent at work and study, at fun and frolic, in the companionship of true Christian gentlemen, and of the lessons we have learned in the classrooms of Christian teachers. Of all this will our Book on Memories tell us in the years to come, and we hope that with the passing of each succeeding twelve-month, we will come to realize more and more thoroughly the lessons that it has to teach.”