John M. Corridan, S.J. '28 (1911-1984) fought against corruption and organized crime on the New York City waterfront. He served as the inspiration for the character of Father Barry in the classic film On the Waterfront. An article about Fr. Corridan, which was first published in the Summer 2009 Regis Alumni News Magazine, is republished below.

The Waterfront Priest

By Tim Peterson '88

Originally published in the

Summer 2009 Regis Alumni News Magazine (Volume 76 | No. 4)

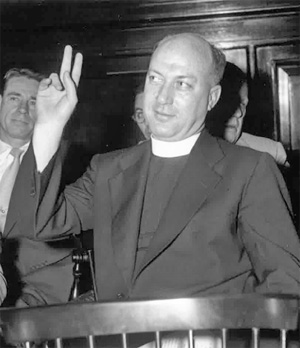

Born 100 years ago, this Irish American of hardscrabble background combined his training in economics and evolving faith to forge alliances in the fight against communism in the labor movement. He would become an indispensible man in this fight and an iconic character on the silver screen. He showed great courage in standing up to the mob and its allies who corrupted the Port of New York, becoming the public face in a fight against the exploitation of longshoreman. He was also a Jesuit, and one of Regis's own.

Born 100 years ago, this Irish American of hardscrabble background combined his training in economics and evolving faith to forge alliances in the fight against communism in the labor movement. He would become an indispensible man in this fight and an iconic character on the silver screen. He showed great courage in standing up to the mob and its allies who corrupted the Port of New York, becoming the public face in a fight against the exploitation of longshoreman. He was also a Jesuit, and one of Regis's own.

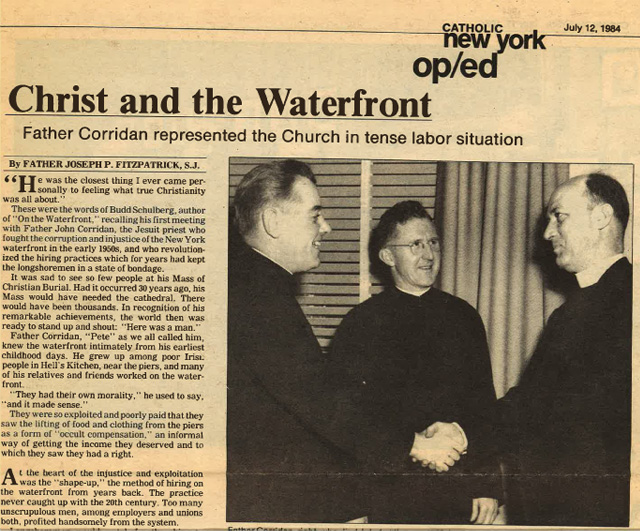

Father John "Pete" Corridan would have turned 100 this year, and if that doesn't strike a chord of memory and reflection from Regis to Red Hook and beyond, it should. At the height of his ministry as "The Waterfront Priest," Fr. Corridan wielded vast influence over labor relations and commerce in the Port of New York. Teaming up with journalist Malcolm Johnson, he shined light on abusive labor practices, ultimately sparking reforms and inspiring screenwriter Budd Schulberg and Director Elia Kazan to create the cinematic masterpiece On the Waterfront.

The son of Irish immigrants, John Corridan was born in Harlem near the Polo Grounds. His father, John Corridan Sr., was a New York City patrolman who died of pneumonia shortly after the birth of his fifth child, leaving a widow and an impoverished family. Despite the economic hardships endured by his family, young John Corridan showed academic promise and was admitted to Regis in 1924, where he, like many Regians before and since, mastered baseball statistics.

After graduating from Regis in 1928, Corridan worked on Wall Street and managed to hold his position into the Great Depression. While impressive in the context of the times, God had much bigger plans. In 1931, Corridan quit his position and entered the novitiate, where he was given the name "Pete" to distinguish him in a class of too many "Johns." The name stuck, and he would be known as Father Pete upon his ordination.

Alarmed by the global rise of anti-clerical communism and its effect of radicalizing workers, the Jesuits began opening "labor schools" in the 1930s to minister to the needs of workers and steer them from communism. Marx had once called religion the "opiate of the people," and his Communist disciples were zealous in their crusade against the Church as a rival for the affections of men. Orthodox Christians in Soviet territory were persecuted, imprisoned and killed. Church property was seized, and whispers of mass killings and other terrors consummated under the rubric of Communism filtered out of the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, fears of a Communist revolution sweeping through Europe were manifest in the rise of two sister statist ideologies then seen as bulwarks against this greater evil—Fascism and Nazism.

Despite Jesuit success in running labor schools such as Xavier Labor School, violence and abuses along the waterfront in the Port of New York had been endemic for decades and defied easy remedy. Rev. Phil Carey, S.J.'25, who ran Xavier Labor School prior to Fr. Corridan's arrival, had trouble connecting with the insular longshoremen until 1946, when Corridan arrived at Xavier.

Irish and from a broken home like many longshoremen, Corridan connected easily with the longshoremen, combining a cool mastery of facts and figures with a steely spirituality and ability (and willingness) to drink, smoke and curse. His ministry at Xavier Labor School was first to teach the men to speak up for themselves, but also to provide a formidable public face with the courage and intellect to front a movement so inimical to the dangerous overlords of the waterfront.

The labor schools and Corridan sought to instill the Catholic Labor doctrine enshrined in the Papal Encyclicals Rerum Novarum and Quadragesimo Anno, which rejected the collectivist vision for common property administered by the state but carefully set forth a vision of labor relations based on dignity of work and the realization that working conditions and moral degeneracy were interconnected. Few settings illustrated this connection better than the waterfront. Through this Catholic doctrinal filter, it took two years ministering to longshoremen at Xavier Labor School before Father Corridan could properly gauge the problems in the area.

Corridan's focus was on the "shapeup," an informal system of hiring for irregular work in which laborers were selected from a much larger gang of dues paying union members. Often seen with unskilled laborers, the shapeup thrived on labor desperation. The hiring foreman was in prime position to take kickbacks from hired workers. Wholly dependent on shipping schedules and the decisions of the hiring bosses for work, many longshoremen spent their ample down time gambling and drinking, often spending themselves into a debt repaid with garnished wages. Working conditions were also unsafe. Injured longshoreman had little recourse for injuries sustained in moving heavy cargo. On a larger scale, the mob-controlled longshoremen's unions could cripple the shipping economy through work stoppages and slowdowns, with ships holding perishable cargo being particularly vulnerable. Theft of cargo was rampant. And from this ill-gotten gain, there was plenty of money to convince politicians to look the other way. In short, a waterfront economy of vice emerged, with a code of silence and suspicion of outsiders enforced through violence.

Corridan's focus was on the "shapeup," an informal system of hiring for irregular work in which laborers were selected from a much larger gang of dues paying union members. Often seen with unskilled laborers, the shapeup thrived on labor desperation. The hiring foreman was in prime position to take kickbacks from hired workers. Wholly dependent on shipping schedules and the decisions of the hiring bosses for work, many longshoremen spent their ample down time gambling and drinking, often spending themselves into a debt repaid with garnished wages. Working conditions were also unsafe. Injured longshoreman had little recourse for injuries sustained in moving heavy cargo. On a larger scale, the mob-controlled longshoremen's unions could cripple the shipping economy through work stoppages and slowdowns, with ships holding perishable cargo being particularly vulnerable. Theft of cargo was rampant. And from this ill-gotten gain, there was plenty of money to convince politicians to look the other way. In short, a waterfront economy of vice emerged, with a code of silence and suspicion of outsiders enforced through violence.

The essence of Corridan's ministry can be distilled from On the Waterfront's famous sermon "Christ in the Shapeup." Borrowing heavily from an earlier Corridan speech entitled "A Catholic Looks at the Waterfront," the scene is set in the open hold of a cargo ship. Longshoreman Kayo Dugan, who was scheduled to testify against the mob-controlled union, lies dead, killed when a cargo sling "accidently" dropped cargo on him. After administering Last Rites, Karl Malden's Fr. Barry looks up at the sullen longshoremen and mob thugs peering down at him and delivers a rebuke to Kayo's murderers and their silent enablers. Comparing the killing of informants to the Crucifixion, Fr. Barry says that those who stay silent share the guilt of it "just as much as the Roman soldiers who pierced the Flesh of Our Lord." Withstanding salvos of thrown fruit and catcalls saying "go back to your Church, Father," Barry reminds the longshoremen that Christ stands with them in the shapeup, a witness to all of its inherent abuse. Christ had the courage to speak up against injustice, regardless of the circumstances, and what Christ would do, Barry says, is what He would have you do.

While the threat of communism in New York was immediate (something verified by famed Communist informer Whittaker Chambers, who operated a mere one block from Xavier Labor School), the anticommunism of the waterfront was purchased at a steep price. In fighting communism, the Church implicitly cast its lot with the anticommunist but corrupt and mob-controlled longshoremen's unions along the waterfront. These unions strongly appealed to the ethnic and religious loyalties of its rank-and-file. Its leaders were typically both outwardly devout and extraordinarily generous Catholics, whose donations lined the waterfront with beautiful churches and filled Church coffers to fund a variety of Church social and education programs. Corridan's efforts were combated within Church hierarchy, and he found himself at odds with Church benefactors and their clerical champions. Taken to an extreme, Corridan and his waterfront competitors staged competing "Communion Breakfasts" in an attempt to win over both the longshoremen and the public at large.

Father Corridan's waterfront ministry might never have achieved its fame were it not for crusading investigative journalist Malcolm Johnson of The New York Sun. Although the lurid violence of the waterfront was obviously a compelling storyline for any journalist, even the New York tabloids couldn't crack the code of silence. Through his ministry, Corridan had gained the trust of numerous longshoremen, thus presenting an opportunity for both Johnson and Corridan to advance their goals. Johnson and the struggling New York Sun exposed the machinations of previously unknown powers on the piers. And for Corridan, cracking a system that fomented sin required the sunlight of publicity, something The New York Sun could readily provide. While most longshoremen were still unwilling to go on the record, Corridan's anonymous sources proved to be excellent for Johnson's purposes. Malcolm Johnson's series "Crime on the Waterfront" was a runaway success, selling newspapers and earning Johnson a Pulitzer Prize in 1949. "Crime on the Waterfront" also shifted public attention to the previously unknown big actors who controlled the piers, several of whom were compelled to testify in front of the New York State Crime Commission in 1952 and 1953. The publicity and testimony eventually lead to the establishment of a Waterfront Commission and banning of the shapeup.

In addition to being excellent journalism, "Crime on the Waterfront" was an excellent story. Hollywood noticed. Budd Schulberg wrote a screenplay based on Johnson's series, collaborating with Corridan in crafting a realistic narrative. It was an unlikely pairing — the secular Jewish Schulberg and director Elia Kazan could scarcely believe a man with the longshoreman persona of Corridan could be a priest in good standing. On the Waterfront cast Marlon Brando as Terry Malloy, a brooding everyman whose brother advanced high in the hierarchy of mobster Johnny Friendly's corrupt union. Given his brother's position, Malloy had every incentive to keep the code of silence but for two factors: one, his burgeoning love interest in Edie Doyle (played by Eva Marie Saint), whose brother was murdered for speaking out, and Karl Malden's Fr. Barry, who teamed with Doyle to nudge Malloy into speaking out.

Released in 1954, On the Waterfront was an overwhelming success, winning eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor, and Best Director. As with "Crime on the Waterfront", Corridan was indispensible for On the Waterfront. Corridan advised Schulberg on the screenplay, helped Kazan find suitable film sets and extras in Hoboken, and even provided Karl Malden with Corridan's own hat and coat for Malden's portrayal of Father Barry. On the Waterfront continues to be considered an all-time cinematic masterpiece. In 1998, the American Film Institute issued a 100-year retrospective listing its top 100 all-time American films. On the Waterfront ranked eighth.

Corridan's success in fighting labor abuses earned him plenty of enemies within the Church hierarchy, and the ground shifted beneath his feet. In 1955, he was transferred to LeMoyne College in Syracuse to teach economics, forever taking him from his ministry on the piers. He later taught theology at St. Peter's College in Jersey City and worked as a hospital chaplain in Brooklyn, closing out his years in a Jesuit nursing home at Fordham University before passing away in 1984.

By some surface measures, John Corridan's ministry ended in failure. While he helped Malcolm Johnson win a Pulitzer Prize and later inspired On the Waterfront, he mostly failed to persuade rank-and-file longshoremen to take actions to help themselves, such as voting to decertify the corrupt International Longshoreman Association's union. Many longshoremen held fast to old traditions, considering Corridan to be a meddler and his call to break the waterfront's code of silence a betrayal of their brethren. Meanwhile, innovation radically changed how ship borne freight was handled. The containerization of cargo in large tractor trailer boxes moved by giant cranes reduced theft of cargo and the need for a large number of men to move relatively small quantities into and out of the hulls of ships. And the longshoremen themselves dreamed bigger dreams for their children, with families leaving the densely packed shore to move to the suburbs. Piers rotted. Life along the waterfront had changed.

But Corridan's ministry was more focused on salvation of souls than mere working conditions. His first ministry at Xavier Labor School was to teach the men to speak up for themselves, face down the code of silence, and band together to fight injustice and the corrosive and dishonest waterfront culture. In short, Corridan encouraged the longshoreman to have the courage of Christ in fighting injustice. In this, he led by example.

Ironically, what made Corridan's ministry so effective also effectively precludes his canonization. Longshoreman felt at ease with this most unusual cleric due in large part to Corridan's shared struggle with alcohol, a trait that does not immediately bring "sainthood" to mind. Coupled with his mercurial politics and controversial battles within the Church, Corridan is unlikely to become Regis's first saint.

But such formalities might not have mattered to Corridan. When considering the question of sainthood for Corridan, his friend Jim Joyce, S.J. said, "Some of them we call saints and some of them are saints that don't need the title. I don't think he needs the title."