Ave atque Vale:

Men for Others in Vietnam

By Paul C. Atkinson ’71

On June 9, 2005, Regis President Rev. Joseph A. O’Hare, SJ ’48 presided at the installation of a plaque at the rear of the chapel. It reads:

their lives for God and Country In Conflicts since 1950

58,000 Americans died in the Vietnam War.

1,741 were from New York City.

Three are listed on that plaque at Regis High School.

While America’s active involvement spanned a decade, the Vietnam War reached a turning point with the outbreak of the Tet Offensive on January 30, 1968. Leading up to the 50th anniversary of this battle, PBS in September broadcast Ken Burns documentary The Vietnam War, a series that explored the human dimensions of the conflict. Mark Bowden published Hue, a detailed account of the month long struggle for the city (which describes the courageous actions of several Jesuit chaplains). Numerous other books and articles have attempted to bring perspective to a conflict that remains controversial in America half a century later.

As this 50 year commemoration of the war unfolded, Regis thought it a fitting time to tell the stories of her three sons.

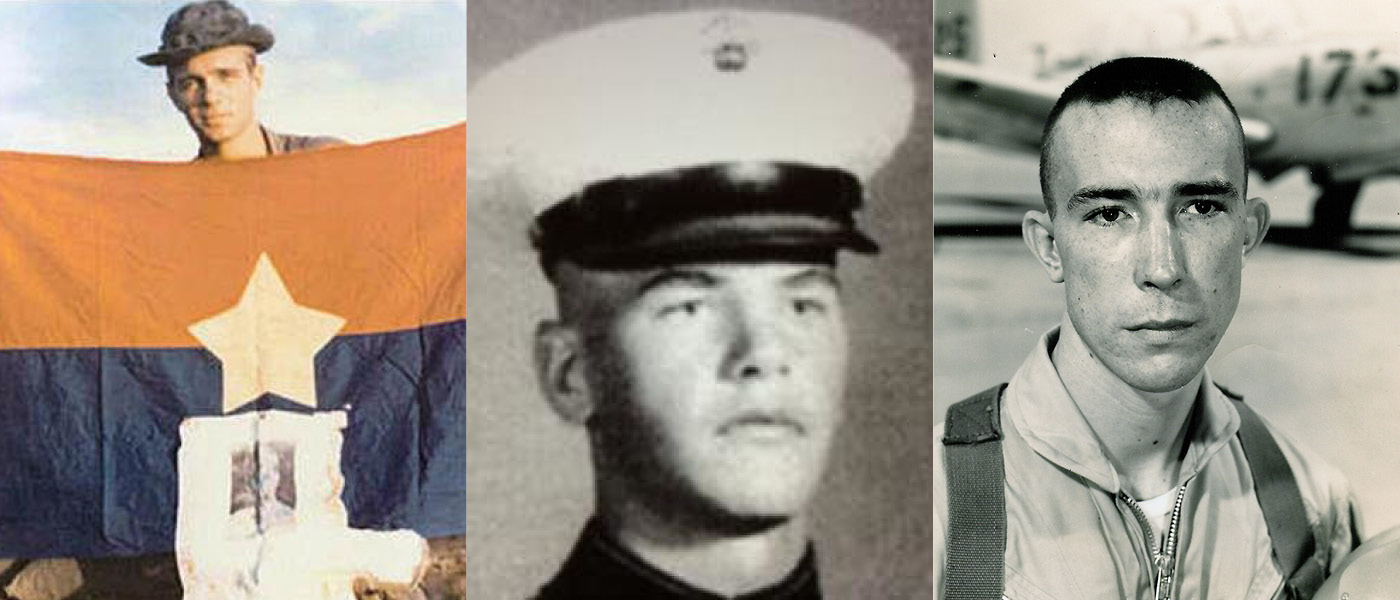

April 10, 1947 – December 14, 1967

Panel 31E, Line 94, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington D.C.

Stephen graduated Regis in 1965, studied for a time at Queens College and was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1966. He underwent basic training at Fort Polk, LA. Upon his arrival in Vietnam on October 10th, 1967, he was assigned to C Company, 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. The unit was based in Chu Chi, northwest of Saigon. Perhaps the Army bureaucracy recognized Stephen’s Regis education, as he was initially selected for training as a supply clerk. But upon arrival in theatre, he was assigned to a ground combat unit. Stephen was killed during a search and destroy mission in Binh Duong province, near Tay Ninh on Thursday, December 14, 1967. For his actions that day he was posthumously awarded a Bronze Star with an Oak Leaf Cluster for Heroism. The citation for that award reads, in part:

Stephen was one of 32 American killed in action that week.

Stephen’s younger brother Douglas, who was serving in the Navy off the coast of Vietnam, accompanied his body home on December 22. The Winter 1968 issue of the Regis Alumni News noted:

He was buried on Saturday, December 23rd, at a Solemn Mass attended by his classmates and six priests from Regis. May he rest in peace.”

The Vietnam War tore America apart. Men in the field were well aware of the divisions back home, and many struggled themselves with the legitimacy of the conflict in which they were engaged. Five weeks after his arrival in Vietnam, Stephen expressed his thoughts in a November 14 letter to his parents, his brother, and his sister Vicki:

Saul Alinsky, the social agitator, once said that no matter how much he criticizes his government, once he has left the United States he suddenly can’t find a nasty thing to say about it.

I am sure that that is what the most sincere people feel, whether liberal or conservative. That is one of the very essences of our nation.”

Victoria Miano was 12 years old when her brother died. As a Gold Star Family member, she has been involved for many years with events focused on the New York City Vietnam Veterans Memorial, a devotion that has kept alive her memories of her brother. But dealing with those memories has not always been easy. In an interview published in the 2017 volume Next of Kin, Vicki spoke with author Inbal Abergil about the challenges of grieving for Stephen in the initial years following his death:

Stephen was born and raised in Jackson Heights. His mother was from Corona; his father was born in Ohio and grew up in Tennessee. Stephen attended Our Lady of Fatima school and entered Regis in the fall of 1961. In sophomore year he opted for the Greek track.

He was elected Vice President of the senior class, and was a member of the Sodality and the Guard of Honor. He ran track, acted in plays, worked on the Owl, and tried the Hearn for one year. His entry in the ’65 yearbook includes a passage from Dryden:

Following his time at Queens College, he spent time at a religious retreat at St. Meinrad’s, a Benedictine seminary in Indiana and may have contemplated a vocation to the priesthood.

On December 14, 2017, members of Stephen’s family and his graduating class gathered for a Mass of Remembrance in the Regis Chapel. Fifty years after his passing, where Stephen’s life may have otherwise taken him is difficult to imagine. His family and those who knew him at Regis in a brief life, cut short by the madness of Vietnam, can cherish their memories and their hopes for his eternal rest.

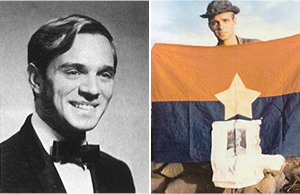

October 23, 1947 – June 3, 1969

Panel 23W, Line 56, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington D.C.

Mike attended the Holy Family parish school in Flushing and graduated Regis in 1963. He attended St. John’s and was awarded a degree in chemistry. One of his fraternity brothers in Phi Kappa Tau remembers him as quiet, a person who “wanted no part of fraternity hazing”.

He initially volunteered for the Marines, but ended up enlisting in the Army and trained as a medic at Fort Sam Houston in Texas. His assignment in Vietnam commenced in April of 1969. According to one of his posthumous citations, he “actively participated in twenty-five aerial missions over hostile territory in support of combat operations of the South Vietnamese army.”

By June 2, Mike’s assignment had shifted. He was serving that day as a medic with Company D, 1ST Battalion (Airmobile), 5th Cavalry Division during a search and destroy mission in Tay Ninh province, the same region where Stephen Pickett had served. It was only Mike’s second experience under fire.

Bill Larsen was the company’s other medic serving with Mike that day. They had gotten to know each other as well as they could under the circumstances. As Bill wrote in a 2004 reminiscence in the San Francisco Chronicle “we covered each other’s back and shared each other’s deepest fears”. In a recent interview, Bill remembered Mike as a “free thinker” who had a “deeper perspective” than other soldiers on life amid the challenges they were experiencing.

Describing the June 2 action, Bill wrote,

Actually, the only thing I could do was slap on a few bandages and return fire in the hopes of keeping our wounded from being wiped out. This worked for a couple of minutes, and then—BANG— a bullet struck my chin, breaking my jaw in half and leaving me face down in a pool of blood. A lifetime later, I awoke to the sound of someone calling my name. Focusing on this sound, I saw Mike crawling toward me with a rifle in one hand and a field dressing in the other. The North Vietnamese soldiers also saw him, and opened the gates of hell unleashing all their dragons; but somehow Mike made it to my side. He released his rifle, and was reaching out with the field dressing to bandage my wound when—BANG—a bullet tore through his left eye...”

Privates Larsen and McParlane were eventually evacuated from the scene. Bill survived; Mike died in the early hours of June 3.

For his actions that day Mike was awarded the Silver Star. The award citation reads, in part:

In addition to the Silver Star, Mike was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star Medal, Air Medal, Purple Heart, Good Conduct Medal and the Combat Medical Badge. Prior to his death, he was awarded the National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal with One Service Star, Vietnam Campaign Ribbon and the rifleman’s Expert Badge.

The Fall 1969 Edition of the Alumni News carried the details of Mike’s passing; in summarizing his service awards, Father Jim Carney SJ wrote:

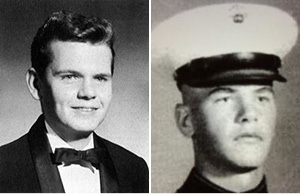

January 3, 1936 – June 1, 1970

Panel 10W, Line 130, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington D.C.

On June 1, 1970, Marine Major Fitzgerald was piloting a CH-46 helicopter near Da Nang in Quang Nam province, assigned to remove a reconnaissance team. During the rescue an anti-personnel mine severely damaged the aircraft and it vibrated uncontrollably. A subsequent citation for Major Fitzgerald’s Distinguished Flying Cross read:

Major Fitzgerald had arrived in Vietnam on January 11, 1970. It was his second combat tour in the country. At the time of his death he was six weeks away from coming home, and had received news of his next assignment: he was to be the new Executive Officer on Marine One, piloting the President of the United States.

On December 3, 1982, the Eastern Regional Headquarters of the Federal Aviation Administration at JFK Airport was dedicated as the Robert M. Fitzgerald FAA Building, in honor of Robert Fitzgerald ’53. His name was chosen by a ballot of employees at the government facility as an individual who “embodied the high goals and ideals the FAA wanted projected for its Eastern Region employees.” Other candidates considered for the honor included Amelia Earhart, Neil Armstrong and the Wright Brothers.

Unlike Steve Pickett and Mike McParlane, Bob Fitzgerald was a career officer. He attended St. Peter’s parochial school in Yonkers. His senior year at Regis, he was a starting guard on a basketball team that went 18-4 and won the Division III CHSAA championship. Team captain and all-city player George Bouvet ’53 remembers, “Bob was good at getting me the ball in the pivot.”

He enrolled at Villanova, transferred to NYU and in 1958 earned an engineering degree. Two older brothers were Marines, one a major, and Bob followed in their footsteps, enlisting in the Corps following graduation. “He wanted to fly” remembers his wife, Irene, a student at Sacred Heart in Yonkers whom he met in the summer of 1952 and married in 1958.

“Bob spoke of Regis often,” recalls Irene. “it was a big part of his life.”

The Marines sent Bob for post graduate study in Monterey CA. Irene recalls a growing Catholic community that was ministered to in missionary-like conditions. “The local priest, Father Sullivan would say Mass in his garage,” she remembers, “and Bob would assist him.”

Bob and Irene moved 13 times over his twelve years in the Corps. He earned his aviator wings in 1962. Bob was away from the family a great deal of the time, including a posting to Christmas Island in the Pacific and an initial tour in Vietnam. Kevin was born in 1962 and Kayleen in 1963; they did not see a great deal of their dad while growing up.

The family was living in California when Bob passed, and relocated to the Washington DC area. His body had not been recovered in time for his funeral service at Arlington Cemetery. When it was, a second service was held. The first service was hard. “The second” Irene recalls, “was very hard.”

Entering second grade in Virginia, Kayleen remembers the ambivalent reaction when she mentioned her father’s passing. “When I said my dad was killed in Vietnam, people seemed awkward and uncomfortable. After a while, I distinctly remember saying to myself ‘Don’t mention it.’” Following the publication of Bob’s obituary, Irene remembers getting one letter that described her husband as a “baby killer.”

In addition to his DFC, Major Fitzgerald was awarded the Bronze Star Medal, the Air Medal, the Navy Commendation Medal and the Purple Heart Medal.

At the December, 1982 dedication of the Fitzgerald FAA building, General P.X. Kelley, Marine Corps Assistant Commandant, summed up Bob Fitzgerald’s career:

“The Foundress and Fr. Hearn could not have conceived that someday boys who went through Regis would become men who gave their lives as tunnel rats in Vietnam. They could not have foreseen all the countless other acts of bravery Regis alumni would be called upon to enact. But it was surely part of their hope that the initiative of their gift would form young men in that great Ignatian tradition of being Men for Others... Young men who, when the choice came, would boldly give of themselves.”

Men who would seek the hero’s part.

Read more Regis news